on caroline polachek, carly rae jepsen, & the ecstatic agony of crushing

how two of 2019's most polished pop albums provide a roadmap to the delirious highs and abject lows of capital-Y Yearning—feat. britney, barthes, and more!

The music video for Caroline Polachek’s “So Hot You’re Hurting My Feelings” takes place in a sherbet-hued vision of Hell, the landscape studded with synthetic stalactites and fluorescent teal sprays of flame. The first time I watched it, I was instantly obsessed—alone in my bedroom, I’d set it on loop and find myself reflexively echoing her steps as she danced across her subterranean prison.

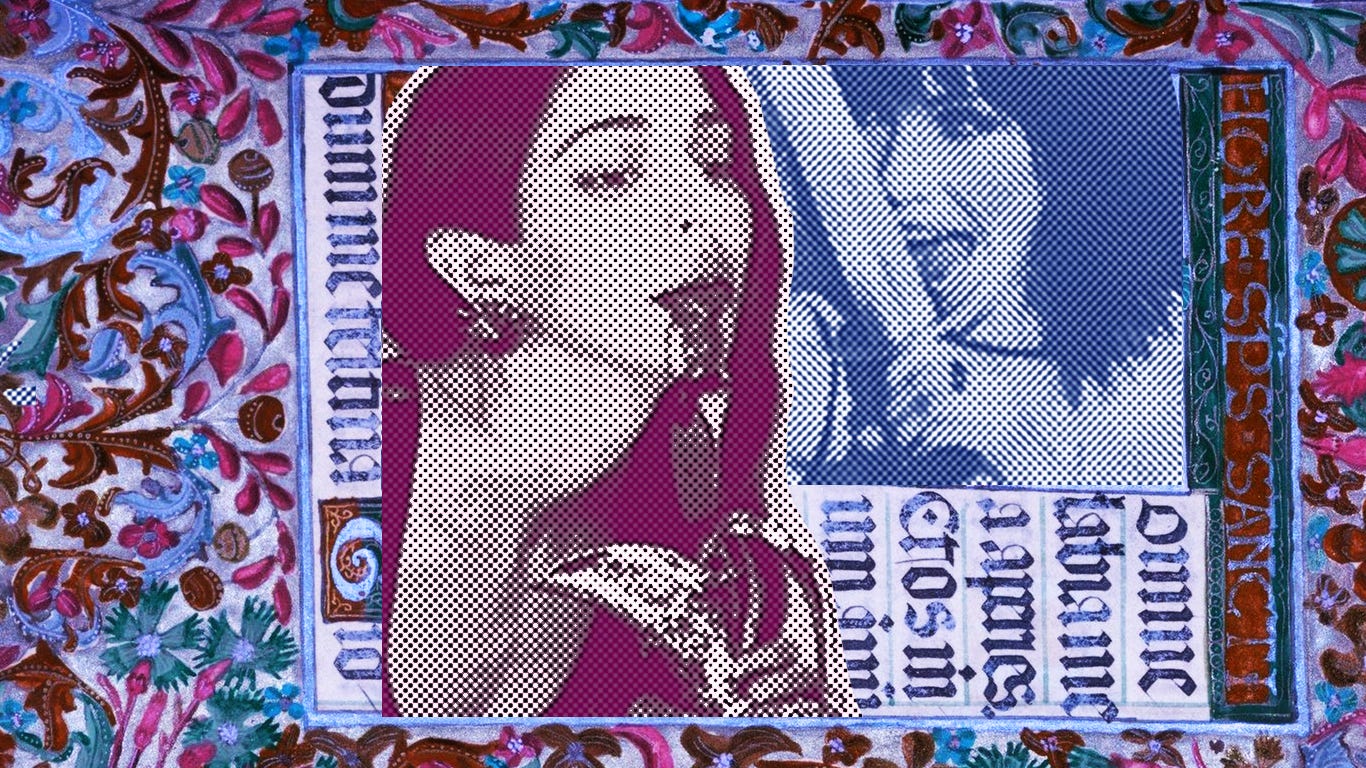

In the video, she has the sinuous, diamond-precise physicality of a Mannerist portrait in motion; her molten gaze and long, dark coils of hair could belong to Domenico Tintoretto’s vaguely goth rendition of a penitent Mary Magdalene. I possess none of Polachek’s grace, and yet I felt something intensely familiar in the way she moved—buoyant but also unquestionably bounded, as if harnessed to some invisible weight. “I get a little bit lonely,” she admits when the chorus begins, her voice seamlessly ascending a stairwell of synths. “Get a little more close to me / You’re the only one who knows me, babe.” When Polachek sings these lines in the video, she places her hands on her stomach and snaps her head back; she could be miming the act of being reeled in on a fishing line or speared through the abdomen.

“So Hot You’re Hurting My Feelings” is one of the most infectious tracks from Pang, Polachek’s first full-length solo outing under her own name. It entered my life with a serendipity that felt almost laser-guided—at the time of its release in October 2019, I was at the apex of an ill-advised infatuation with one of my friends, whom I was intermittently sleeping with but spent much more time being a general nuisance to. The entire situation had the feeling of an excruciatingly bad long-form comedy bit that I was never sure how much sincerity I was supposed to be committing to, but I also really wanted to be kissed. The distinguishing feature of any desire, after all, is its tendency to make you deeply stupid.

Each time that irresistible hook hits—“So hot you’re hurting my feelings! Can’t deal!” – it sounds a little more urgent; it’s easy to believe this longing really is immolating her from the inside out. The song’s bridge is built from a soaring, quasi-operatic vocal run that somehow sounds both anguished and euphoric; Polachek’s voice is searing, yet underneath the melody she keeps chanting “show me your banana” in a way that feels giddily shameless (or at least like a wry, tongue-in-cheek acknowledgment of how ridiculous it feels to want anyone so much). The next iteration of the chorus ends on a sharp, breathless gasp that feels like the sonic equivalent of realizing oh, no – I really do like them!

In her work as part of the band Chairlift, Polachek’s voice forms the vessel for numerous pristine exercises in yearning. Their breakout hit “Bruises” is the one that sticks in most people’s memory for its abridged usage in a 2008 Apple iPod Nano advertisement, but the full track feels more melancholy than commercial-friendly confection. The way she coos that chorus oozing with vowels—“so black and blue-ooh / for you-ooh”—feels like an enchantment you can’t escape. The lyrics describe an inventory of minor wounds willingly incurred for a beloved, the kind of fatalistic optimism of learning gymnastics for someone who won’t even bother to walk your way.

Likewise, my favorite Chairlift songs lie in staunchly tenderhearted territory. The sweet, shimmering “I Belong in Your Arms” blooms into a chorus that feels like a late-career Cocteau Twins track on ecstasy, describing the kind of connection that feels strong enough to melt the entire world away beyond the circumference of an embrace. “Crying in Public,” in its serene resignation to the indignity that comes with realizing just how sincerely you want someone, could be an ever-so-slightly more forlorn precursor to “So Hot You’re Hurting My Feelings.” “Sorry I’m crying in public this way,” Polachek apologizes, though her voice is lofty and crystalline rather than heavy with despair. “I’m falling for you, I’m falling for you.” The YouTube thumbnail for the music video is a close-up of her eyes luminous with drops of mingled tears and rain; she could be a contemporary Our Lady of Sorrows in a mint-green hoodie.

Throughout Pang, Polachek continues to narrate romantic desire in a way that feels loosely chained to some degree of agony. The album’s name comes from a feeling that she describes in an interview with PopCrush as an “intense, urgent kind of internal hunger […] that kind of pricks you emotionally from the inside.” It’s the kind of clarity that strikes in the middle of the night, long before you feel consciously willing to acknowledge your heart’s compulsions. In the title track, she casts this hunger as a “beautiful knife cutting right where the fear should be” atop an intro that, with its twinkling electronic chimes and gloss of processed vocals, could be an eccentric descendant of Owl City’s 2009 smash-hit “Fireflies” (an imagined connection that, in itself, makes me feel mournful for a time that now feels impossibly distant).

The chorus, with its mirrored refrain of “into me / and I go into you,” could be an easy euphemism, but it’s also gripping enough to be read literally—the first time I heard it, I felt like I could see my own desire as a series of palpable thresholds, both concrete and exacting enough in its attention to materialize as the arcaded halls of a cathedral. Every time Polachek utters the word “pang!” it reverberates like a self-contained seismic wave, its precision a crucial part of its capacity to devastate. When she asks “What can I not destroy for you?” in the second verse, it’s undeniably an invitation.

While listening to Pang, I spent a lot of time considering desire in the sacred as well as erotic sense. One of the aftershocks of an even vaguely Catholic upbringing—you can take the girl out of after-school catechism classes, but you can never really extract the catechism from the girl—is that the only feeling that ever rivals the intensity of a full-blooded crush is the simultaneous certainty that you ought to suffer for it. “I’m beginning to see why I would have been drawn to monastic life if I lived in the Middle Ages,” I’d written in one of my most vainglorious diary entries, attempting to dissect the agony of having a crush so incomprehensible he might as well have been God to my pitifully adolescent, rat-brained self. “As a girl, that pure unadulterated capacity for want inside me feels so intense that faith in a higher power would be the only vessel large enough to even begin comprehending it.”

I found myself unironically identifying with Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, a monumental masterpiece of Baroque sculpture completed in 1652 that portrays the eponymous saint swooning in seemingly-orgasmic rapture as an angel aims a spearhead at her heart. The piece directly adapts a scene from Teresa’s autobiography, completed in the mid-16th century, in which she describes a visionary encounter that left her inflamed with love for God: “The pain was so great, that it made me moan; and yet so surpassing was the sweetness of this excessive pain, that I could not wish to be rid of it.” Similarly, Polachek’s melancholy “Ocean of Tears” begins with her warning a lover that “This is gonna be torture / before it’s sublime.” The chorus wears its heart on its sleeve, professing “Oh my god, I wanna know what it feels like!” to have unmediated intimacy with someone, right before cresting into an outstretched, otherworldly oooh anchored by primordial surges of bass.

Polachek’s lyrics also recall the writings of Mechthild of Magdeburg, a 13th-century German mystic who articulated religious enlightenment through metaphors charged with a decidedly erotic understanding of pain. In one chapter of The Flowing Light of the Godhead, a work she began around 1250 to describe her visions of God, she describes the soul “[rising] to the heights of bliss and to the most exquisite pain when she becomes truly intimate with him.” Elsewhere, she takes on the perspective of the soul itself, who describes herself as “wounded to the death / By the beam of your fiery love. / Now you leave me, Lord, lying in my misery, / My wounds untended, in great torment.”

On one level, this mindset could read as a fundamentally misogynistic fetishization of female suffering, but I’ve always thought Mechthild was touching upon a universal experience: the feverish shock of surrendering wholeheartedly to your longing for anyone (or anything) that feels unreachable. In “Hit Me Where It Hurts,”Polachek taps a similar vein, imploring her lover to “go on and hit me in the heart, hit me where it hurts.” In its verses, her voice goes low and throaty as she lists phrases that conjure the language of being hunted: “bullseye, dead end,” “moving target,” “blind spot, Achilles' heel,” “long shot, left field.”

Within pop music, this kind of rhetoric is hardly novel. To name just one obvious example, the title of “Hit Me Where It Hurts” naturally conjures up associations with Britney Spears’ debut single “ ... Baby One More Time,” released when Spears herself was only sixteen. The song is grounded in an unforgettable three-note piano riff—B-flat followed by double Cs that come down like anvils—and rippling wah guitars. It’s rendered downright addictive by Spears’ coy, slyly warped delivery, which lands heavy on the tongue with no sharp edges. As someone who’s always reveled in the insufferable game of attempting to close-read a crush in the same way one might approach a particularly dense literary text, the way she wails, “Just give me a si-i-ign!” sounds like something I’ve been reaching for my entire life.

Likewise, Roland Barthes’ A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments casts lovers and neurotic literary theorists as possessors of the same gaze: “I look for signs, but of what? What is the object of my reading? Is it: am I loved (am I loved no longer, am I still loved)? Is it my future that I am trying to read, deciphering in what is inscribed the announcement of what will happen to me, according to a method which combines paleography and manticism? Isn't it rather, all things considered, that I remain suspended on this question whose answer I tirelessly seek in the other's face: What am I worth?” In his immaculate 2008 debut single “Crush”—a song whose chorus begs to be sung along with ardent, soaring falsetto and histrionic gesticulations whenever you’re lucky enough to hear it—American Idol season seven runner-up David Archuleta echoes the same anxieties: “Do you catch a breath when I look at you? Are you holding back like the way I do?” Asymmetric desire is its own private, agonizing kind of pleasure; at its most thorough, it’s a combination of piety and hermeneutics. You know you’re ensnared when you feel like the world’s most insufferable semiotician.

At the same time I was listening to Pang on repeat and engaging in embarrassing levels of cathexis towards someone who clearly wasn’t going to do the same for me (more out of oblivion than malice, to be clear, which somehow always feels more demeaning to the person trying to do the reading), I spent a lot of time telling my friends how I’d rather be repeatedly socked in the jaw instead of continuing to feel this way, like I was actually a medieval flagellant trying to exorcize my fleshly appetites by any means possible. Lately, amidst this indefinite stretch of a summer under quarantine, that degree of gluttony for punishment has only amplified among the people I know—the inherent futility of the quest for new subjects to orient our seething, heedless desires towards is precisely what makes it so thrilling.

“Crush is rendered cute, brief, and pathologically girlish instead of passionate, enraged, and at the very core of what, in the midst of vulnerability, keeps us going day after day,” writes Tiana Reid in a dazzling essay for The New Inquiry, mediating on how the crucial fervor (and perhaps even insurrectionary potential) that lies behind all crushes is often defanged by its association with childish frivolity. “To say ‘I have a crush’ is to feel forced upon, a reminder of dispossession, yes, but also a small glimpse of possibility, that alchemical feeling of vitality so foolishly powerful that I live for it.”

The same impulse, I think, is what makes Polachek’s rigorous renditions of heartache feel so striking—her songs encourage us to fundamentally inhabit that kind of human fallibility rather than stifle it, to revel in the wondrously irrational joyride that comes with infatuation. “Hit Me Where It Hurts,” after all, balances out the masochistic tendencies of its title by encouraging its subject to “just ride it out, ride it out.” If yearning for someone you can’t be with really is a “private kind of hell,” in Polachek’s words, you might as well dance while you’re trapped inside.

If Polachek’s music is a stiletto, then Carly Rae Jepsen’s is a glorious sledgehammer. In a piece for The Awl in 2015, the year Jepsen’s cultishly revered album Emotion was released, Jia Tolentino compared her songs’ sense of annihilating hunger to the way female mystics have theorized the pursuit of divine love. “The love of Carly Rae’s sonic imagination is distinctly spiritual: directed with unimaginable force at some distant object, further distinguished by having no subjectivity at all,” she writes. On Dedicated, her fourth studio album released four years later, that force is still vividly present—but as the purposefulness of that title suggests, Jepsen’s desires feel even more intense here because of their precise focus.

Within her cosmology, the Platonic-ideal circumstances of a crush are always just unknowable enough to twist into full-throated fantasy at the slightest touch—a framework I found deeply relatable. The friend I’d had feelings for a lifetime ago was deeply impassive and handsome in a way that came off as simultaneously babyish and brooding; he was capable of both incredible consideration and a kind of sitcom-esque haplessness so staggering it occasionally made me fear for his life. As with the fuzzy beloveds who abound within Jepsen’s discography (“Julien” is her sole song to bestow its subject the distinguishing feature of a name), his opacity rendered him a more perfect object of desire even as it frustrated me to no end.

Dedicated is bursting with odes to a brand of untempered devotion that I’ve always been inclined to, more invested in the anxious rapture of pursuit than the domestic resolution of being happily caught. It feels more transcendent than horniness, though being flagrantly horny can certainly be a part of it; “Want You in My Room,” the first song produced for Jepsen by Jack Antonoff, specifies its title request with “on the bed, on the floor!” in a bombastic, jubilant chorus that eventually explodes into a saxophone outro. Yet that increased confidence also comes with a greater willingness to articulate the ache of romantic unfulfillment. In “The Sound,” she doesn’t hesitate to say “God, you make me so tired!” to an aloof lover; the skittish, ska-inflected “I’ll Be Your Girl” is Jepsen at her most deliciously unhinged, seeing red and breathlessly “banging on your door, calling out your name” as she wrestles with the jealousy of seeing someone she cares for with someone new.

One of her most compelling dramatic scenarios comes in “Happy Not Knowing,” an airy, disco-brushed earworm about being determined not to form a deeper attachment to another person (thematically, it could be a companion to Robyn’s “Hang With Me,” a 2010 club track spangled with arpeggios that warns a new friend not to fall “recklessly, heedlessly in love with me”). “I fight, I fight, I fight my feelings for you, all night,” the song begins, the repetitions punctuated by abrupt, low-pitched synth spasms that mirror the lyrics’ spirit of suppression. The chorus starts with a breezy, preemptive denial: “But if there's something between you and me, / Baby, I have no time for it.”

Her voice is bright and bouncy, but there’s also a twinge of affectedness to her delivery, as if she’s trying to make herself believe it. “And please don’t stir it up, / I’m sure it’s nothing but some heartburn, baby,” she sings sweetly. It’s the aural equivalent of appending ha ha, just kidding … unless? to a suggestive text. “I'm afraid, afraid, afraid, afraid of knowing what I'm knowing, what I'm knowing,” Jepsen finally confesses in the bridge, her voice falling as she moves into more vulnerable territory with the small, tender thrill of being let into a secret.

Still, I think the album’s most transportive song is “Too Much,” which feels like both an exaltation and lament in its articulation of what it feels like to be a young woman who can’t help being immoderate in all her appetites. In comparison to the cliff’s-edge leaps of ecstasy that characterize tracks like “Run Away With Me” or “Cut to the Feeling,” “Too Much’s” sonic architecture feels more deceptively unassuming — it begins with staccato stabs of synth that serve as the entire song’s vertebrae, steady underneath the climbing melodies. Yet something mesmeric locks into place after the chorus repeats a couple of times; the constancy of the beat begins to feel like the only thing tethering Jepsen to earth.

“The deeper her wounds become, the more violently she struggles. The more loving God is to her, the higher she soars,” Mechthild writes in The Flowing Light of the Godhead, describing a believer's punishing path to divine bliss. “The more ardent she remains, the sooner she bursts into flames. In the radiantly expectant pre-chorus of “Too Much,” Jepsen croons, “Cause when I get so low, it takes me higher / I'm not afraid to know my heart's desire—ooh-ah!” I think this stream of heat is what, in various concentrations, fuels all these songs—it’s the awful tension of being aware that the continued pursuit of something you want will probably end painfully, even as your heart drags you into its orbit with the force of an entire planet’s magnetic field.

Last summer, I’d traveled to see Jepsen live on tour with a few friends (including, incidentally, a former crush) and we’d miraculously squeezed ourselves into the front row, woozy with liquor and adrenaline. The moment we heard that warbling electronic heartbeat that begins “Too Much,” some Dionysian floodgate burst within us. I felt temporarily displaced from my body, my jaw unhinging to screech “When I feel it, then I feel it too much!” with a ferocity that contorted my entire face in service of tearing the sound out. Something inside me had clicked into place and sent me reeling. I felt a glittering, almost cruel conviction that I would always be a girl encapsulated by the general intemperance of this moment—someone whose dignity would always be foreclosed by the depth of my appetite, displaying an ungainly degree of effort even in this moment of paramount joy.

To me, this potential to induce feelings of wrenching, violent rapture has always been present in Jepsen’s work. Even in “I Really Like You,” the lead single from Emotion and a track whose exhilaration derives purely from a bloodless, sugar-sweet rush of wanting, there’s a trace of grisliness in the first lines of the bridge: “Who gave you eyes like that, said you could keep them?” It feels like a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it acknowledgment of the eldritch viciousness at the heart of any fixation with someone who gives nothing away: the horror that comes with recognizing the total senselessness of your hunger, the urge to violently disassemble the forces that draw you to someone against all logical thought.

In truth, the most frenzied, intimate, and precious romances of my life have been friendships, particularly with those who share my qualities of indelible too-muchness. Still, the most torturous aspect of any all-consuming longing can be that you end up missing the sheer rigor of its misery once it lapses into something more comfortable—the moment you realize you’ve turned from valiant hairshirt-wearer back into just another girl in a sweater, if this transformation was a less gratifying Cinderella story. The lacuna is less about the individual themselves than the shape of wanting they once carved out within you. It’s the same childish sensation that comes in the immediate aftermath of losing a baby tooth, worrying the empty socket with your tongue where there used to be an aching weight and only finding void.

Both Polachek and Jepsen are flawless narrators of that incipient wanting, the kind that makes you see someone across a crowded room and suddenly know—with a small, selfish switchblade flick of recognition—that you wish they were only paying attention to you. I’ve experienced this many times before and am certain I will again and again, but the most striking aspect of this feeling is in how intensely it hits each time. It’s a gem-grade cut of emotion so saturated it makes you think you’ll never feel anything this deeply ever again, even as you’re aware of how theoretically ridiculous that is; it’s the giddy, sublime stupidity of being in your early twenties and believing every low-grade heartache you’ve ever endured is both utterly unprecedented and the most cataclysmic tragedy in recorded history.

This past spring, during my last semester of college—a time that now itself feels like a quaint historical moment to be studied from afar, rather than a lived experience of fairly recent memory—one of my professors asked us a question that she said, in turn, a former professor had once posed to her. “Would you rather be the lover or the beloved?” I’d known my answer in a second. I’d happily flounder in the deep ends of unrequited desire for the rest of my life if it meant I’d never have to relinquish the ability to narrate how it feels, to retain that elastic capacity to keep seeing the entire world remade through the prism of adoration. If not love, what else is worth annihilating yourself for?

fantastic! i went from never having listened to any of Caroline Polachek's work, to listening to most of the album in time with reading about the songs as you mention them to get the full experience, and i'm completely sold. the piercing obsession with 'So Hot You're Hurting My Feelings' hit me full force all at once, just as you said it had for you. i sat there stunned-- how had i never seen this before?

and just the same, your writing style and art history references have captured me just as Polachek has, i absorbed this article, completely stunned, knowing i was woefully hooked the second you described the So Hot video as a living mannerist painting. so perfectly apt. talk about the highs and lows of infatuation when this is the only essay you have on here! i neeeeed more!!

subscribing <3